The School of History, Philosophy, and Religion at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon invites applications from specialists in Buddhist Studies (Asian Buddhism) for a full-time tenure-track appointment at the Assistant Professor level, effective September 16, 2016.

Category Archives: Buddhism

Expert knowledge in Sanskrit texts —additional sources

In my previous post on this topic, I had neglected an important source and I am grateful for a reader who pointed this out. The relevant text is a verse of Kumārila’s (one of the main authors of the Mīmāṃsā school, possibly 7th c.) lost Bṛhaṭṭīkā preserved in the Tattvasaṅgraha:

The one who jumps 10 hastas in the sky,

s/he will never be able to jump one yojana, even after one hundred exercises! (TS 3167)

Why did Vedānta Deśika care about Nyāya? (CORRECTED)

Readers may have noted that I am working on the hypothesis that Veṅkaṭanātha/Vedānta Deśika priviledged the Pūrva Mīmāṃsā system, on the basis of which it rebuilt Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta. This would be proved by the preeminence of Mīmāṃsā doctrines in Veṅkaṭanātha’s works, but also by his several works dedicated to Mīmāṃsā. But then, one might argue, what about Veṅkaṭanātha’s engagement with Nyāya? Is Nyāya just a further addition or does Nyāya (also) lie at the center of Veṅkaṭanātha’s project?

Are words an instrument of knowledge?

Kumārila's Śabdapariccheda

Are words an instrument of knowledge? And, if so, what sort of? Are they an instance of inference insofar as one infers the meaning on the basis of the words used? Or are they are an independent instrument of knowledge, since the connection between words and meanings is not of inferential nature?

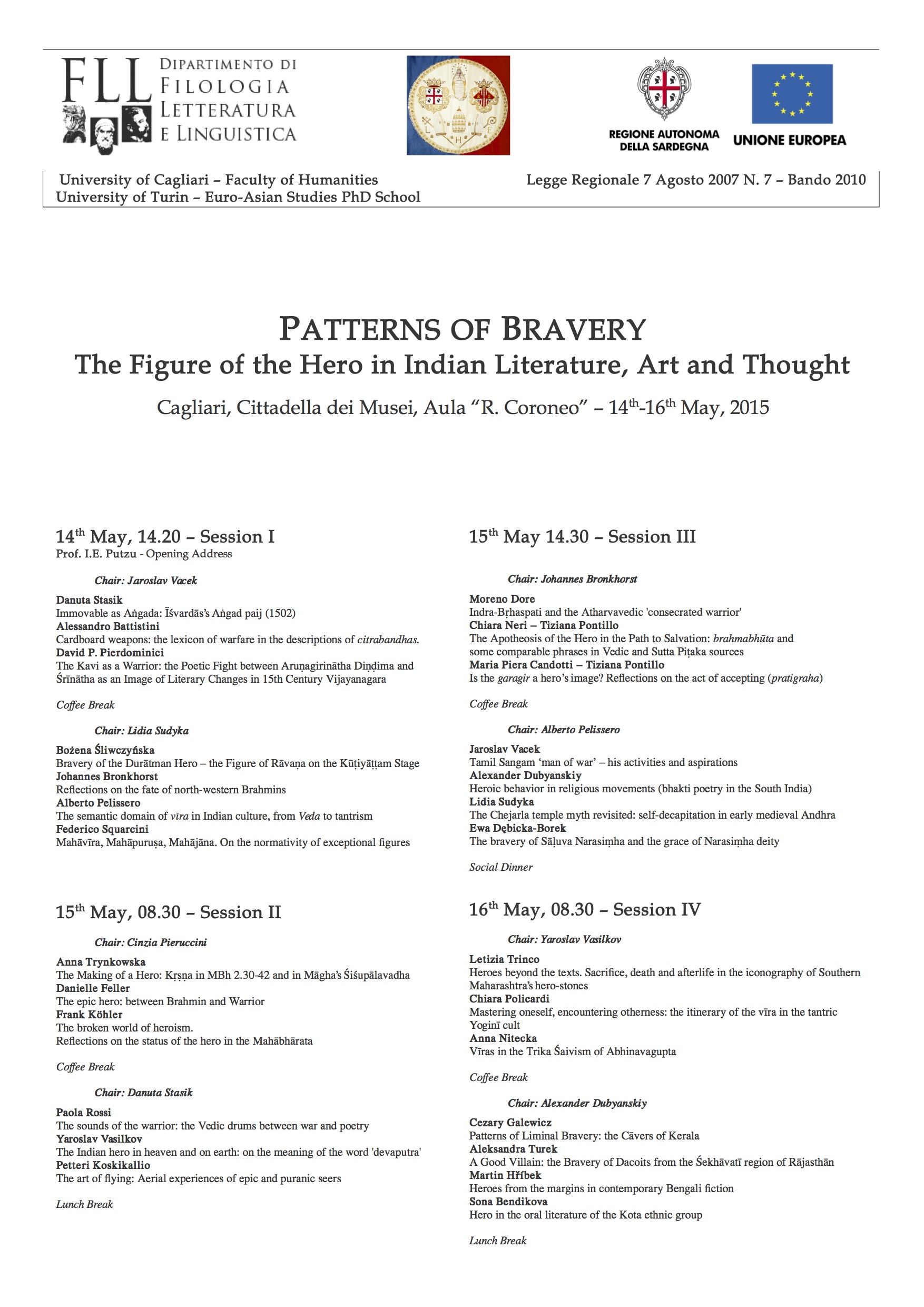

Patterns of Bravery. The Figure of the Hero in Indian Literature, Art and Thought

Cagliari, 14th--16th May 2015

Tiziana Pontillo signalled me the conference mentioned in the title. You can download the flyer here.

From the point of view of methodology, let me praise T. Pontillo for the fact that she will give two joint papers. Let us all learn from each other and dare more cooperative work (if we enjoy it)!

Workshop “Language as an independent means of knowledge in Kumārila’s Ślokavārttika“

Workshop

Language as an independent means of knowledge in Kumārila’s Ślokavārttika

| Time: | Mo., 1. Juni 2015–5. Juni 2015 09:00-17:00 |

| Venue: | Institut für Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Seminarraum 2 |

| Apostelgasse 23, 1030 Wien | |

| Organisation: | Elisa Freschi |

Topic

During the workshop, we will translate and analyse the section dedicated to Linguistic Communication as an instrument of knowledge of Kumārila Bhaṭṭa’s (6th c.?) Ślokavārttika. The text offers the uncommon advantage of discussing the topic from the point of view of several philosophical schools, whose philosopical positions will also be analysed and debated. Particular attention will be dedicated to the topic of the independent validity of Linguistic Communication as an instrument of knowledge, both as worldly communication and as Sacred Texts.

Detailed Contents

Ślokavārttika, śabdapariccheda,

v. 1 (Introduction)

v. 3–4 (Definition of Linguistic Communication)

v. 15 (Introduction to the position of Sāṅkhya philosophers)

vv. 35–56 (Dissussion of Buddhist and Inner-Mīmāṃsā Objections)

vv. 57ab, 62cd (Content communicated by words and sentences) [we will not read vv. 57cd–62ab, since they discuss a linguistic issue]

vv. 63–111 (Discussion of Buddhist Objections)

Commentaries to be read: Pārthasārathi’s one (as basis) and Uṃveka’s one (for further thoughts on the topic)

X-copies of the texts will be distributed during the workshop. Please email the organiser if you want to receive them in advance.

For organisative purposes, you are kindly invited to announce your partecipation with an email at elisa.freschi@oeaw.ac.at.

The present workshop is the ideal continuation of this one. For a pathway in the Śabdapariccheda see this post.

Some common prejudices about Indian Philosophy: It is time to give them up

Is Indian Philosophy “caste-ish”? Yes and no, in the sense that each philosophy is also the result of its sociological milieu, but it is not only that.

Is Indian Philosophy only focused on “the Self”? Surely not.

Is there non-processed perception? The McGurk effect

The McGurk effect is a well-known experiment in which, while hearing a given phoneme and seeing someone pronouncing another phoneme, we “hear” the second one instead of the first one, the correct one. This seems to mean that the auditory perception of a phoneme is already processed, it is savikalpa. Try the McGurk effect in the following video:

Now, the problem is that, after many trials, this does not work with me. I guess that this might have to do with the fact that I am not an English Native speaker and that, accordingly, I process the image of someone pronouncing the second phoneme in a non-automatic way (after all, /f/ as pronounced in my native language is probably not pronounced with the same lip movement).

What do you think, does it work with you? If yes or if no, what is your native language

Necessity in Mīmāṃsā philosophy

Anand Vaidya has recently raised a very intriguing discussion on modality in Indian philosophy. His post started with the suggestion that modality is less central in Indian philosophy than it is in Western thought. In the comments, several scholars suggested examples hinting at reflections on modality also in Indian thought but, now that I think again about them, they mostly discussed the modality of possibility in Indian thought. What about necessity?

A pathway through Kumārila’s Ślokavārttika, śabda-chapter, part 1

The chapter on śabda ‘language as instrument of knowledge’ within Kumārila’s Ślokavārttika is an elaborate defense of linguistic communication as an autonomous instrument of knowledge. Still, its philosophical impact runs the risk to go unnoticed because it is at the same time also a polemical work targeting rival theories which we either do not know enough or we might be less interested in, and a commentary on its root text, Śabara’s Bhāṣya on the Mīmāṃsā Sūtra. The chapter has also the further advantage that all three commentaries on it have been preserved. Thus, beside Pārthasārathi’s useful one, one can benefit also from Śālikanātha’s deeper one and from Uṃveka’s commentary, which is the most ancient, tends to preserve better readings of the text and is philosophically challenging.

The following is thus the first post in a series attempting a pathway through the chapter: