I am currently working with some amazing colleagues at the Vienna University of Technology on the formalisation of Mīmāṃsā deontic logic (for further information, read this post). One of the problems we are facing is that duties prescribed in Vedic prescriptions appear to be interpreted as regarding only specific eligible people, the adhikārins. For instance, one needs to perform a Kārīrī sacrifice if one desires rain, so that the duty to perform it does not apply generally to all. Even in the case of a sacrifice one has to perform throughout one’s life, such as the Agnihotra, the same restriction applies, since Mīmāṃsā authors interpret it as meaning that one has to perform it if one desires happiness, i.e., throughout one’s life, since one always desires happiness.

Category Archives: Philosophy

Garfield (and Daya Krishna) on intercultural philosophy and the power of languages

Jay Garfield’s research may interest you or not, but his methodological musings are worth reading anyway. Here I linked to the interview where he compared the exclusion of Indian philosophy from syllabi, justified on the basis of the fact that there are already enough Western philosophers to work on and one does not have time to focus on anything else, to the exclusion of female philosophers based on the motivation that “We have already enough men whose works we need to study”.

Now, I have just read (the German translations of) an article of him on Polylog 5 (2000), which recounts his adventures in intercultural philosophy.

There is honey on the tree in your backyard; why are you going to the mountains in search of honey? The principle of parsimony in Mīmāṃsā

“If you can find honey on a tree nearby, why going to the mountains?”

arke cen madhu vindeta, kim artham parvataṃ vrajet

What do I obtain if I refrain from eating onion (and so on)?

In the case of the Śyena and the Agnīṣomīya rituals, violence is once condemned and once allowed, causing long discussions among Mīmāṃsā authors. Similarly, the prohibition to eat kalañja, onion and garlic is interpreted differently than the prohibition to look at the rising sun. Why this difference?

Hermeneutic principles in Mīmāṃsā

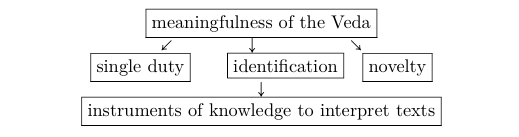

The hermeneutic principles are the ones which regard only the Brāhmaṇa texts and whose significance could not be automatically extended outside them, e.g., to a different corpus of texts, or can be extended, but regard characteristics of language. Mīmāṃsā authors had to develop them first of all out of an epistemological concern, namely because they considered the prescriptive portion of the Veda authoritative and thus needed to distinguish the authoritative portion of the Veda.

Consequently, in order to make sense of complex texts like the Brāhmaṇas, in which it is not at all easy to distinguish what belongs to a certain ritual and what to another, Mīmāṃsā authors needed to be able to distinguish the boundaries of a given prescriptive passage. Consequently, some basic hermeneutical rules regard the identification of single prescriptions through syntax and through the unity and novelty of the duty conveyed.

In the following list I tried to enumerate the cornerstones among the hermeneutic principles.

- The prescriptive portion of the Veda is never meaningless.

- A prescriptive sentence is identified through the syntactical expectations among the words forming it and through the single purpose it conveys (PMS 2.1.46).

- Each prescription must be construed as prescribing a new element. Seeming repetitions must have a deeper, different meaning, e.g., enhancing the value of the sacrifice to be performed.

- Each prescriptive text, which may entail several prescriptions is construed around a principal action to be done.

- Each prescription conveys (only) a single piece of deontic information (anyāya ankekārthatva, ŚBh ad PMS 2.1.12; vākyabheda, ŚBh ad 1.1.1).

- No prescription can be meaningless. If it appears to be meaningless, it is not a prescription (vidhiś cānarthakaḥ kvacit tasmāt stutiḥ pratīyeta, PMS 1.2.23).

- Each prescription should promote an action (āmnāyasya kriyārthatvād ānarthakyam atadarthānāṃ tasmād anityam ucyate, PMS 1.2.1).

- The most powerful instrument of knowledge for knowing the meaning of a prescription is what it directly states (śruti), which is most powerful than its implied sense, context, syntactical connection, etc. (niṣādasthapatinyāya PMS 6.1.51–52).

- A material may achieve a result resting on an already prescribed act, like a king’s officer can achieve a certain result only insofar as he relies on the king’s authority (Vṛttikāra within ŚBh ad PMS 2.2.26).

- Any prescribed action needs to have a result. If a prescribed action seems to have no result, postulate happiness as the general result (viśvajinnyāya).

- Only what is intended (vivakṣita) is part of the prescription. For instance, in sentences such as ”Take your bag, we need to go”, the singular number in ”bag” is not intended. What is prescribed is to take one’s bag or bags, and not the fact that one must take one bag only. By contrast, the singular number is intended in ”You must take one pill per day”, meaning that one has to swallow exactly one pill per day. Whether something is intended or not is determined through its link with the sentence’s principal duty.

This post is a follow-up of this one (on logical and hermeneutical principles in Mīmāṃsā).

Conveying prescriptions: The Mīmāṃsā understanding of how prescriptive texts function

The Mīmāṃsā school of Indian philosophy has at its primary focus the exegesis of Sacred Texts (called Vedas), and more specifically of their prescriptive portions, the Brāhmaṇas. This means that the epistemic content conveyed by the Vedas is, primarily, what has to be done. In order words, the Veda is an epistemic authority only insofar as it conveys a deontic content.

Ontology is a moot point if you are a theist

A philosopher might end up having a double affiliation, to the philosophical standpoints shared by one’s fellow philosophers, and to the religious program of one’s faith.

This can lead to difficult reinterpretations (such as that of Christ with the Neoplatonic Nous, or that of God with the Aristotelic primum movens immobile), or just to juxtapositions (the addition of angels to the list of possible living beings).

A Vaiṣṇava who starts doing philosophy after centuries of religious texts speaking of Viṣṇu’s manifestations (vibhūti), of His qualities and His spouse Lakṣmī (or Śrī or other names), is in a similar difficult situation.

Confluence: A new journal on comparative philosophy

How did comparative philosophy evolve in the last sixty+ years? What is the difference between intercultural philosophy and comparative philosophy? All the answers can be read in the introductory essay to the first number of a new journal dedicated to comparative philosophy, namely Confluence.

The long and learned introductory essay, by Monika Kirloskar-Steinbach, Geeta Ramana and James Maffie (who are also the journal’s editors)

Ritual prescriptions in Śrautasūtras: Why they are interesting (first part)

I am working on the formalisation of the prescriptions regarding the Full- and New-Moon sacrifices in the Baudhāyana Śrautasūtra. In Kashikar’s edition, they cover about 32 full pages of Sanskrit. And they are overtly boring in their pedantic prescription of each sacrificial detail. Thus, instead of reading the BaudhŚrSū, have a look at what follows for what is interesting in them: