“If you can find honey on a tree nearby, why going to the mountains?”

arke cen madhu vindeta, kim artham parvataṃ vrajet

Category Archives: Mīmāṃsā

What do I obtain if I refrain from eating onion (and so on)?

In the case of the Śyena and the Agnīṣomīya rituals, violence is once condemned and once allowed, causing long discussions among Mīmāṃsā authors. Similarly, the prohibition to eat kalañja, onion and garlic is interpreted differently than the prohibition to look at the rising sun. Why this difference?

Hermeneutic principles in Mīmāṃsā

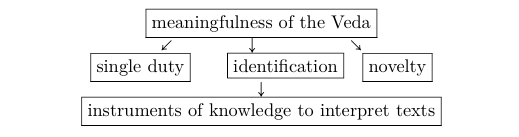

The hermeneutic principles are the ones which regard only the Brāhmaṇa texts and whose significance could not be automatically extended outside them, e.g., to a different corpus of texts, or can be extended, but regard characteristics of language. Mīmāṃsā authors had to develop them first of all out of an epistemological concern, namely because they considered the prescriptive portion of the Veda authoritative and thus needed to distinguish the authoritative portion of the Veda.

Consequently, in order to make sense of complex texts like the Brāhmaṇas, in which it is not at all easy to distinguish what belongs to a certain ritual and what to another, Mīmāṃsā authors needed to be able to distinguish the boundaries of a given prescriptive passage. Consequently, some basic hermeneutical rules regard the identification of single prescriptions through syntax and through the unity and novelty of the duty conveyed.

In the following list I tried to enumerate the cornerstones among the hermeneutic principles.

- The prescriptive portion of the Veda is never meaningless.

- A prescriptive sentence is identified through the syntactical expectations among the words forming it and through the single purpose it conveys (PMS 2.1.46).

- Each prescription must be construed as prescribing a new element. Seeming repetitions must have a deeper, different meaning, e.g., enhancing the value of the sacrifice to be performed.

- Each prescriptive text, which may entail several prescriptions is construed around a principal action to be done.

- Each prescription conveys (only) a single piece of deontic information (anyāya ankekārthatva, ŚBh ad PMS 2.1.12; vākyabheda, ŚBh ad 1.1.1).

- No prescription can be meaningless. If it appears to be meaningless, it is not a prescription (vidhiś cānarthakaḥ kvacit tasmāt stutiḥ pratīyeta, PMS 1.2.23).

- Each prescription should promote an action (āmnāyasya kriyārthatvād ānarthakyam atadarthānāṃ tasmād anityam ucyate, PMS 1.2.1).

- The most powerful instrument of knowledge for knowing the meaning of a prescription is what it directly states (śruti), which is most powerful than its implied sense, context, syntactical connection, etc. (niṣādasthapatinyāya PMS 6.1.51–52).

- A material may achieve a result resting on an already prescribed act, like a king’s officer can achieve a certain result only insofar as he relies on the king’s authority (Vṛttikāra within ŚBh ad PMS 2.2.26).

- Any prescribed action needs to have a result. If a prescribed action seems to have no result, postulate happiness as the general result (viśvajinnyāya).

- Only what is intended (vivakṣita) is part of the prescription. For instance, in sentences such as ”Take your bag, we need to go”, the singular number in ”bag” is not intended. What is prescribed is to take one’s bag or bags, and not the fact that one must take one bag only. By contrast, the singular number is intended in ”You must take one pill per day”, meaning that one has to swallow exactly one pill per day. Whether something is intended or not is determined through its link with the sentence’s principal duty.

This post is a follow-up of this one (on logical and hermeneutical principles in Mīmāṃsā).

Conveying prescriptions: The Mīmāṃsā understanding of how prescriptive texts function

The Mīmāṃsā school of Indian philosophy has at its primary focus the exegesis of Sacred Texts (called Vedas), and more specifically of their prescriptive portions, the Brāhmaṇas. This means that the epistemic content conveyed by the Vedas is, primarily, what has to be done. In order words, the Veda is an epistemic authority only insofar as it conveys a deontic content.

A new project on Veṅkaṭanātha’s aikaśāstrya

I just received the unofficial (but wonderful) news that the Elise Richter project I submitted to the FWF has been accepted!

You can read the general abstract below:

Anand Venkatkrishnan on Vedānta, bhakti and Mīmāṃsā through the history of the family of Āpadeva and Anantadeva in 16th–17th c. Banaras

When, where and how did bhakti become acceptable within the Indian intellectual élites?

Veṅkaṭanātha’s epistemology, ontology and theology

In the world-view of a fundamental Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta teacher like Vedānta Deśika (1269–1370, aka Veṅkaṭanātha), theology is the center of the system and epistemology and ontology assume their role and significance only through their relationship with this center.

Mīmāṃsā and Grammar

Did Mīmāṃsā influence Indian Grammar? Or did they both develop out of a shared prehistory?

Long-time readers might remember that this is one of my pet topics (see this book). Probably due to the complex technicalities involved, apart from Jim Benson, not many people have been working on this topic, but in the last few days I had the pleasure to get in touch with Sharon Ben-Dor (who worked on paribhāṣās, more on his articles in a future topic) and then to receive the following invitation:

Doing things another way: Bhartṛhari on “substitutes” (pratinidhi)

Time: Friday, 17. October 2014, Beginn: 15:00 c.t.

Place: Institut für Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Seminarraum 1, Apostelgasse 23, 1030 Wien

Speakers: Vincenzo Vergiani and Hugo David (Cambridge)

Enough with the “eternality of sound” in Mimamsa!

F.X. D’Sa Sabdapramanyam in Sabara and Kumarila (Vienna 1980) is one of the very first books on Mimamsa I read and I am thus very grateful to its author. Further, it is a fascinating book, one that —I thought— shows intriguing hypotheses (e.g., that Sabara meant “Significance” by dharma) which cannot be confounded with a scholarly philological enquire in the texts themselves.

Andrew Ollett has just posted some interesting comments on K. Yoshimizu recent workshop and on the impact of his theories from a linguistic point of view. Andrew especially elaborates on the topic-comment opposition and on the possibility to read along these lines the vidheya–upadeya opposition found in Kumarila.

If you missed the workshop, you can read about it also here.