This is more or less the thesis advanced by Jayarava in his longest comment on this post.

The idea is that the (Buddhist) religion is primarily experiential and that philosophy is a later reification which misses the main point at stake and moves the emphasis away from what really counts. Moreover, in the case of Buddhism (but I am inclined to think that no other theology would survive Jayarava’s analysis) the result is full of inner contradictions and does not stand a critical inquire.

Thus, why engaging in philosophical thought, if you care for a given religion? Why entering a field in which you will loose anyway, since sooner or later a new development in, say, physics or neurosciences will show that you are at least partly wrong?

A possible answer would be to claim that natural sciences and theology do not speak about the same things (a claim Jayarava appears to refute). Moreover, one might claim that human beings naturally try to understand (as in Aristotle). But are there positive reasons for engaging in philosophy if one comes from a religious standpoint? Let us consider Giordano Bruno’s paradoxical words on this topic (as you will all know, Giordano Bruno was a Catholic priest and philosopher who was burnt on 17.2.1600 because of his heretic ideas —this sonet praises the ignorance of those who do not question anything, as if this were a moral virtue):

IN LODE DELL’ASINO:

Oh sant’asinità, sant’ignoranza,

Santa stoltizia, e pia divozione,

Qual sola puoi far l’anime si buone,

Ch’uman ingegno e studio non l’avanza!

Non gionge faticosa vigilanza

D’arte, qualunque sia, o invenzione,

Né di sofossi contemplazione

Al ciel, dove t’edifichi la stanza.

Che vi val, curiosi, lo studiare,

Voler saper quel che fa la natura,

Se gli astri son pur terra, fuoco e mare?

La santa asinità di ciò non cura,

Ma con man gionte e ’n ginocchion vuol stare

Aspettando da Dio la sua ventura.

Nessuna cosa dura,

Eccetto il frutto dell’eterna requie,

La qual ne done Dio dopo l’esequie!

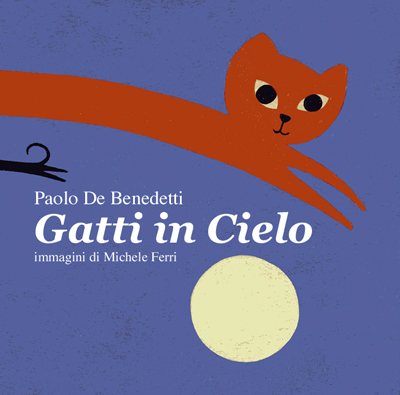

is well-known especially for his studies on Hebraism, but here I would rather like to remember him for his articles and books on animals’ and plants’ theology. This is a problem which is much less evident in South Asian religions, given the general acceptance of a (hierarchical) continuity between animal and human lives. Yet, as already discussed here, the same continuity is not generally accepted in the case of plants.

is well-known especially for his studies on Hebraism, but here I would rather like to remember him for his articles and books on animals’ and plants’ theology. This is a problem which is much less evident in South Asian religions, given the general acceptance of a (hierarchical) continuity between animal and human lives. Yet, as already discussed here, the same continuity is not generally accepted in the case of plants.