The topic is not explicitly discussed, as far as I know, in European or American epistemologists (who all seem to assume that it obviously is), whereas it is relevant in South Asian epistemology of language.

Category Archives: Philosophy

“But is Indian thought really philosophy?”

We can answer the question “What is it?” for a religion or worldview by proceeding either sociologically or doctrinally. […] In philosophy, for example, the question “But is it philosophy?” can be not so much a question about the boundaries of the discipline taken doctrinally as it is a rejection of any approach not already favored by the elite in power, In that case, the genus within which the question “But is it philosophy?” falls is not philosophy but rather politics, or maybe even just bullying. (Eleanore Stump 2013, pp. 46, 48).

Animal theology

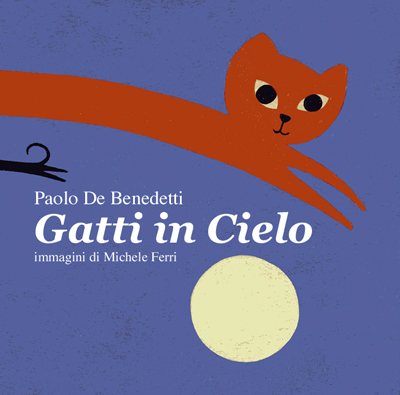

Paolo De Benedetti's death

The news of the death of Paolo De Benedetti reached me while I was reading a short book of him (E l’asina disse…).

Paolo De Benedetti  is well-known especially for his studies on Hebraism, but here I would rather like to remember him for his articles and books on animals’ and plants’ theology. This is a problem which is much less evident in South Asian religions, given the general acceptance of a (hierarchical) continuity between animal and human lives. Yet, as already discussed here, the same continuity is not generally accepted in the case of plants.

is well-known especially for his studies on Hebraism, but here I would rather like to remember him for his articles and books on animals’ and plants’ theology. This is a problem which is much less evident in South Asian religions, given the general acceptance of a (hierarchical) continuity between animal and human lives. Yet, as already discussed here, the same continuity is not generally accepted in the case of plants.

De Benedetti used Singer’s arguments about suffering as the distinctive character shared by all living beings and keeping them alike. Unlike Singer, however, De Benedetti saw the commonality of animals, human beings and plants in a theological perspective: They are all created, not natural beings and their being alive is what God has donated to them.

Analytical Philosophy of Religion with Indian categories

Wednesday and Thursday last week I enjoyed two days of full immersion in the Analytical Philosophy of Religion. In fact, the conference I was attending was about the ontological status of relations from the perspective of Analytical Philosophy of Religion and most speakers started their talk saying that they were not experts in the one or in the other field. I was neither nor, which made me the sub-ideal target for all talks —and yet one who could learn a lot from all.

A few random remarks:

- “God” is an ambiguous term, in fact so ambiguous that I wonder why does not each study about philosophy of religion start with a discussion of what the author means by this word. I pragmatically distinguish between god as devatā ‘deity’ (a superhuman being which is better than a human one, but only insofar as s/he has the same qualities of a human being in higher degree, like the Greek and Roman deities of mythology), god as īśvara ‘Lord’ (the omniscient and omnipotent being of rational theology), god as brahman ‘impersonal being’ (the impersonal Absolute of most monisms, including Bradley’s one discussed by Guido Bonino) and god as bhagavat ‘personal God’ (the personal God one directly relates to in prayers, without necessarily caring for His/Her omnipotence or omniscience, but rather focusing on Him/Her as spouse, parent, child, etc.). Within this classification, Analytical Philosophy of Religion appears to focus on the īśvara aspect of God.

Ontology of relations in Analytical Philosophy of Religion

Wednesday and Thursday there will be a conference entitled Relatio Subsistens in Verona (Italy). I am looking forward for the chance of discussing the Viśiṣṭādvaita concept of apṛthaksiddhatā ‘indissolubility’ between God and knowledge in Analytical terms.

What counts as philosophy?

On the normative disguised as descriptive (SECOND UPDATE)

As a scholar of Prābhākara Mīmāṃsā I am well aware of how the normative is often disguised as descriptive. “It is seven o’ clock” says the mother, but what she means is rather “Get up! You have to go to school”.

The subject as knower and doer in Yāmuna’s Ātmasiddhi

Again on the ontology of qualities and substances

Opponents coming from the Advaita field figure often in Yāmuna’s Ātmasiddhi, which shows that even before Rāmānuja Vaiṣṇava authors were taking seriously the challenge of Advaita. Even more interesting is the way Yāmuna answers to them. Let us see some examples concerning the concept of self (ātman):

[Obj.:] But the fact of being a cogniser is the fact of performing the action of cognising and this implies modifications and is (typical of) insentient things and belongs to the sense of Ego.

Viśiṣṭādvaita and Nyāya on qualities UPDATED

Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta authors claim that the whole world is made of the brahman and that everything else is nothing but a qualification of it/Him.

This philosophical-theological concept, it will be immediately evident, crashes against the (Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika) idea of a rigidly divided ontology, with substances being altogether different from qualities. In other words, the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika world if seen from outside is similar to the world of today’s folk ontology, the one influenced by scientism, while its structure resembles the one of Aristotle’s ontology.

What is a commentary? UPDATED

And how the Nyāyamañjarī and the Seśvaramīmāṃsā do (not) fit the definition

What makes a text a “commentary”? The question is naif enough to allow for a complicated answer. First of all, let me note the obvious: There is not a single word for “commentary” in Sanskrit, where one needs to distinguish between bhāṣyas, vārttikas, ṭippanīs, etc., often bearing poetical names, evoking Moons, mirrors and the like.

Podcasts on Indian philosophy: An opportunity to rethink the paradigm?

Some readers have surely already noted this series of podcasts on Indian philosophy, by Peter Adamson (the historian of Islamic philosophy and Neoplatonism who hosts the series “History of philosophy without any gaps” —which I can not but highly praise and recommend, and which saved me from boredom while collating manuscripts) and Jonardon Ganeri.

The series has several interesting points, among which surely the fact of proposing a new historical paradigm (interested readers may know already the volume edited by Eli Franco on other attempts of periodization of Indian philosophy, see here for my review). They explicitly avoid applying periodizations inherited from European civilisations, and consequently do not speak of “Classical” or “Medieval” Indian philosophy. What do readers think of this idea? And of the podcast in general?

I have myself a few objections (which I signalled in the comment section of each podcast), but am overall very happy that someone is taking Indian philosophy seriously enough while at the same time making it also accessible to lay listeners. In this sense, I cannot but hope that Peter and Jonardon’s attempts are successful.

The series includes also interviews to scholars: Brian Black on the Upaniṣads, Rupert Gethin on Buddhism, Jessica Frazier on “Hinduism” (the quotation marks are mine only), myself on Mīmāṃsā. Further interviews are forthcoming. Criticisms and comments are welcome! (but please avoid commenting on my pronunciation mistakes.)