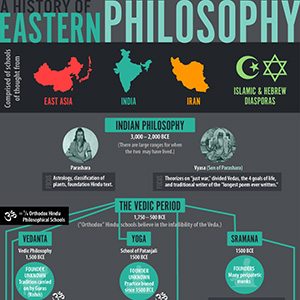

Most readers will have already noted this chart of “Eastern Philosophy” at Superscholar.

Now, I have already commented about it at DailyNous, but the staff of Superscholars has written to me twice to advertise the map, so that I feel compelled to repeat my comment and some further ones here. I would also like to ask readers: Do you think these maps have some use at all? If so, for whom? Beginners or Advanced scholars?

The first problem regards the very scope of the chart, i.e., its being “Eastern”. “Eastern Philosophy” is a geographic abstraction at best unapplicable to philosophy and at worse very misleading —for reasons pointed out by Manyul Im and Malcolm Keating on the DailyNous, i.e., it makes one assume similarities which are not there and overlook similarities between, e.g., the Greek and the Islamic world, which are there.

As for Indian Philosophy, the ancient part is just plainly wrong (see also Malcolm’s comments reproduced here). There is so little to rescue, that it does not make sense even to try. By contrast, the more recent part (on the schools of Vedānta) is still very misleading (what should it mean that in Dvaita “There is a strict distinction between two equally real worlds: one, the Brahman and two individual people”?), but might have some initial value as a draft upon which one should improve.

Since I am not competent enough about Chinese philosophy, let me quote Manyul Im’s aphoristic comment (also from DailyNous):

This may be the worst chart of East Asian philosophy ever. Super Scholar is neither.

On the same website you can find several other comments, ranging from misspelt Chinese characters to misunderstood concepts… Moreover, Tibetan, Japanese and Korean philosophies are altogether absent.

Thus: If you teach an “Eastern Philosophy”, warn your students!

Heh. They wrote to me as well. I append my response:

My blog is for my essays which do usually have an image for decoration. But I’m concerned to see such wildly inaccurate information in your info graphic. That version of Indian history is the one promoted by Hindu Nationalists. It has no basis in fact. A couple of examples:

The Ṛgveda was composed ca 1500-1200 BC, whereas Patañjali lived ca 150 BC.

The consensus date for the Buddha these days is ca. 480-400 BC.

Zoroaster by contrast is thought to have flourished ca 1000-1200 BC (you have him both as 1800BC and as a 6th century BC thinker)

If anything the Ājivakas were associated with Jainism and were certainly not an offshoot of Buddhism!

Also the lines of development look confused to me – untidy in a way that is unhelpful in an infographic.

The lines are all the same colour which is confusing as it suggests a relationship beyond a simple geographical one. There seems to be no consistent relationship between time and the vertical axis.

In what way is the Arthaśastra (accurately dated to ca. 300 BC) related to the founding of the sthavīra lineages of early Buddhism? [It isn’t!]

Why do the lines at the beginning of the emergence of sectarian Buddhism form a triangle? What does that communicate?

Why is the Dharmaguptaka line in red? What does that communicate?

The graphic is visually confusing and factually inaccurate. So thanks for contacting me, but no, I won’t be using your infographic or linking to your website as things stand.

Thank you, Jayarava. Your answer is probably the best thing to do. Still, I wonder who did the chart and how could no one realise that it is so wrong. Even Wikipedia would have been enough to check it!

I don’t really want to defend the infographic, but your strongest point might be that it’s visually confusing, since you seem to have been rather confused by it. Several of the “errors” you point out are in fact errors of your own reading. The chart does not show the Ājivakas as an offshoot of Buddhism, for instance, and neither is the Arthaśastra linked to Buddhism. (The Dharmaguptakas are in red, presumably, because of the connection with China; doesn’t make much sense, granted, but it’s clear why they’ve done it.)

The “Islamic” probably falls into the “not even wrong” land. Arabic/Islamic philosophy, as commonly understood, simply does not exist within the chart.

Elisa, thanks for this post. There are, as you say, so many thing wrong with the graphic that it’s hard to know where to begin.

As for whether these charts are useful, I can see a few ways where they might be:

1. A historical timeline of important figures. I have something hand-written on my office wall that compares major figures in Greek and and European philosophy to South Asian philosophers and some major world events. This kind of chart would be especially helpful for introducing students to the context of thinkers, although it would be important to emphasize that the dialectic between texts can cross geographic and temporal gulfs!

2. A conceptual diagram of divisions between “schools.” This would, of course, be simplified, but it can be useful to map the broad relationships between the “āstika” and “nāstika”, the Buddhist schools, etc. This kind of chart would be helpful, again, for introducing students to some of the crucial distinctions between groups of thinkers. However, to be successful, it would have to choose the appropriate scope–this chart tries to go too deep and too broad at the same time. Further, it’s important to emphasize how these groupings are determined–are people self-reflectively deciding to be part of a tradition, are later thinkers putting them into a tradition, what gets to count as a relevant similarity, etc. There could be a historical dimension to this, like (1), but keeping it conceptual rather than historical makes clear what is being analyzed.

3. A commentarial diagram showing relationships between texts. This would be complicated, but maybe could be developed using software that allows the viewer to zoom in and out at different levels. This kind of diagram would probably only be helpful, in detail, for specialists, although maybe some kind of big-picture chart could be used to show introductory students the complexities of the commentarial tradition in Indian philosophy. There’s a chart someone developed for biblical contradictions (at least, contradictions by someone’s lights): http://www.chrisharrison.net/index.php/Visualizations/BibleViz

In my former, pre-academic life, I worked with data analysis and reporting, so I am very attracted to clear visualizations of complex information. However, it’s very difficult to do this in a way which is accurate and visually compelling. One of the best sites for this kind of thing is http://www.informationisbeautiful.net/

Eventually, I would like to be able to create (or help someone create) teaching and research aids which are at the level in the sites above. However, it would require more thought about the purpose and scope of the chart. And starting with the goal of showing “Eastern philosophy” is going to result in something terrible, regardless of the efforts put in.

Thank you, Malcolm, this is all very interesting (I did not even know you had had a pre-academic life!). I agree with you that a crucial point is (the choice of the topic and) the distinction between the meaning of the lines. While it may make some sense to connect a guruparamparā, for instance, the meaning of lines we might draw between rival traditions which nonetheless influenced each other (say, the Mahābhārata and the Buddhist Canon according to Hiltebeitel’s hypothesis) would have to be completely different (and readers would need to be warned about what is meant by the ones or the others).

I am also a big fan of visual aids, although I usually use them to represent ideas, (e.g., the way the anvitābhidhāna theory works, compared to the abhihitānvaya one) not summaries of schools. Let me know if you go on with your project of creating visual aids which would be more ambitious.

Elisa, yes, I like using visual aids for concepts, too (I’d be interested in seeing what you use for the theories you mention, actually). As long as our aids are clearly just that–aids in understanding a concept–I think a lot of angles can be useful: cartoons, diagrams, metaphors, audio, etc.

And on my pre-academic life, I did database design and data analysis for a big company in the US. It involved programming, working with spreadsheets, as well as translating complex ideas into a format accessible to corporate decision-makers. This was after my undergraduate and before my master’s degree (actually during, too–I worked 40 hours a week while finishing my master’s). I think it’s given me an appreciation for how my undergraduate students can employ the skills I teach them even if they never pick up another philosophical text in their lifetimes…though, of course, I hope they will.

(& I’ll definitely let you know about future projects with visual aids.)