First, some perspective: “Wikipedia’s list of ancient Greek philosophers (seemingly based on Anthony Preus’ books) lists 316 authors –of many of them not a single work survived. How many works and authors do you think are covered by the label ‘Sanskrit philosophy’?” When I asked this question in class, I got answers ranging from 5 (!) to 312 authors. Karl Potter’s Bibliography of Indian Philosophy (by no means complete) lists 9,631 authors.

A further important point in this connection: Sanskrit philosophy does not only deal with “religious topics” (although religion is discussed in it!). There is a big emphasis on philosophy of language and epistemology, plenty of ontology and logic and then many other philosophical discussions (the only topics being relatively neglected are political philosophy, as well as philosophy of race, of gender etc.).

Thus, we are dealing with a world, geographically, chronologically and culturally comparable with “European philosophy” (400 BCE–1900 CE). Thus, just like no one would expect you to master the latter after a term, so don’t expect that a class will be enough to master “Sanskrit Philosophy”.

In a nutshell: Invest some time with the topic and make fun of whoever among your colleagues thinks that Sanskrit philosophy is a smaller field than “Philosophy of the young Wittgenstein”.

Second, why should you at all want to undertake such a journey? For a few reasons: 1. Sanskrit philosophy (like other philosophical traditions) will enrich you with a treasure-house of new questions and answers. 2. No matter what you will specialise in, having a perspective from far away will shatter your prejudices and make you aware of your unconscious biases.

Third, what does it take? Will you need to learn the relevant languages? Will it be hard? Answer: It will be hard, because philosophy is hard. If it looks easy, you are not trying hard enough. But it should not be harder than any other philosophical tradition, apart from extra-philosophical elements, such as getting accustomed to the idea that male names end with -a. You do not need to learn the relevant languages, although I will encourage you to learn Sanskrit if you will decide to specialise in the field in three years.

Forth, should you decide to specialise in a historically underrepresented philosophical tradition, let me warn you about something else. You will be “hireable” by departments of areal studies (and/or religious studies) as well as of philosophy. This is due to the fact that in the last decades scholars of Sanskrit philosophy have not been mainly hired by philosophy departments, but often by “Asian studies” or “Religious studies” ones. (I will not discuss the reasons for such historical circumstances.) This also means that you will end up having to convince two different sets of people that you are a serious scholar. You will need to show that you are accurate and sensitive to the context when talking to the first group of colleagues, while at the same time needing to show to your philosophical colleagues, every year again, how philosophically cool is what you are doing.

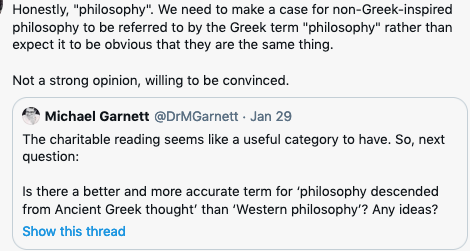

The UofT is not like that, so I routinely forget and am chilled again when colleagues point out that it is not at all obvious that there is “philosophy” outside of the Euro-American world, see below for a nice example (I don’t want to engage with mean or plainly racist cases):

To summarise: If you’ll specialise in Sanskrit philosophy, you will be cheered up by a vibrant community (it’s a small world, apart from India, so we are all very welcoming), and you’ll have the wonderful experience of being a pioneer in many respects (there are literally MILLIONS of texts which expect to be properly studied!). But, you’ll have to learn to deal with objections like the ones I mentioned above.

Colleagues and students: What did I forget?