The Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta is a philosophical and theological school active chiefly in South India, from the last centuries of the first millennium until today and holding that the Ultimate is a personal God who is the only existing entity and of whom everything else (from matter to human and other living beings) is a characteristic.

Category Archives: Vaiṣṇavism

Andrew Ollett’s Review of Duty, Language and Exegesis in Prābhākara Mīmāṃsā

Reviews on Duty, Language and Exegesis in Prābhākara Mīmāṃsā: Many thanks and some notes —UPDATED

Most of my long-term readers have had enough of my discussions of Prābhākara Mīmāṃsā, of its late exponent Rāmānujācārya, and of its theories about deontic logic, philosophy of language and hermeneutics. They may also know already about my book dedicated to these topics. More recent readers can read about it here.

You can also read reviews of my book by the following scholars:

- by Taisei Shida on Vol. 31 of Nagoya Studies in Indian Culture and Buddhism. Saṃbhāṣā (2014), pp. 84-87.

- by Andrew Ollett on Vol. 65.2 of Philosophy East and West (2015), pp. 632–636 (see here)

- by Gavin Flood on Vol. 8.3 of Journal of Hindu Studies (2015), pp. 326–328, (the beginning is accessible here)

- by Hugo David on the vol. 99 of BEFEO (2012-13), pp. 395-408 (you can read the beginning here)

I am extremely grateful to the reviewers (I could not have hoped for better ones!) for their careful and stimulating analyses and for their praising my attempts to make the text as understandable as possible and to locate sources and parallels in the apparatus. In fact, as a small token of gratitude for the time they spent on my book, I will dedicate a post to each one of their reviews, where I discuss their corrections and suggestions. The first one in this series will appear next Friday.

What happened at the beginnings of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta?—Part 2

Several distinct component are constitutive of what we now know to be Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta and are not present at the time of Rāmānuja:

- 1. The inclusion of the Āḻvār’s theology in Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta

- 2. The Pāñcarātra orientation of both subschools of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta

- 3. The two sub-schools

- 4. The Vedāntisation of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta

- 5. The impact of other schools

What happened at the beginnings of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta?—Part 1

The starting point of the present investigation is the fact that between Rāmānuja and Veṅkaṭanātha a significant change appears to have occurred in the scenario of what was later known as Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta (the term is only found after Sudarśana Sūri). The Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta as we know it was more or less there by the time of Veṅkaṭanātha, whereas in order to detect it in the oeuvre of Rāmānuja one needs to retrospectively interpret it in the light of its successive developments. This holds true even more, although in a different way, for Rāmānuja’s predecessors, such as Yāmuna, Nāthamuni and the semi-mythical Dramiḍācārya etc.

16th World Sanskrit Conference: A panel on the development of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta

Last week took place one of the main (or the main?) conferences for Sanskrit scholars, namely the 16th edition of the World Sanskrit Conference, of which you can read a short summary by McComas Taylor on Indology (look for it here). Marcus Schmücker and I organised a panel called One God—One Śāstra, Philosophical developments towards and within Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta between Nāthamuni and Veṅkaṭanātha. You can read the initial call for papers here.

How Vedāntic was Yāmuna?

Was Rāmānuja the first author of the Vedāntisation of the current(s) which later became well-known as Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta? Possibly yes. But, one might suggest that there are many Upaniṣadic quotations also in Yāmuna’s Ātmasiddhi and that Rāmānuja’s Śrībhāṣya seems to speak to an already well-established audience, and I wonder how could this have been the case if he were the first one attempting the Vedāntisation…

Loving God for no reason

Why does a devotee love God? Because He is good, merciful, omniscient…? Or just out of love?

This seems to be one of the moot issues between the two currents within the form of Vaiṣṇavism later to be known as Śrīvaiṣṇavism, since Piḷḷai Lokācārya (13th c.) stresses that loving without reason is superior to loving with a reason, just like Sītā’s ungrounded love for Rāma is superior to that of Lakṣmaṇa, who loves Rāma for his good qualities (see Mumme 1988, p. 150).

Two (or three) different narratives on Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta etc.

Some authors tend to think that once upon a time there was one Yoga and that later this has been “altered” or has at least “evolved” into many forms. According to their own stand, they might look at this developments as meaningful adaptations or as soulless metamorphoseis.

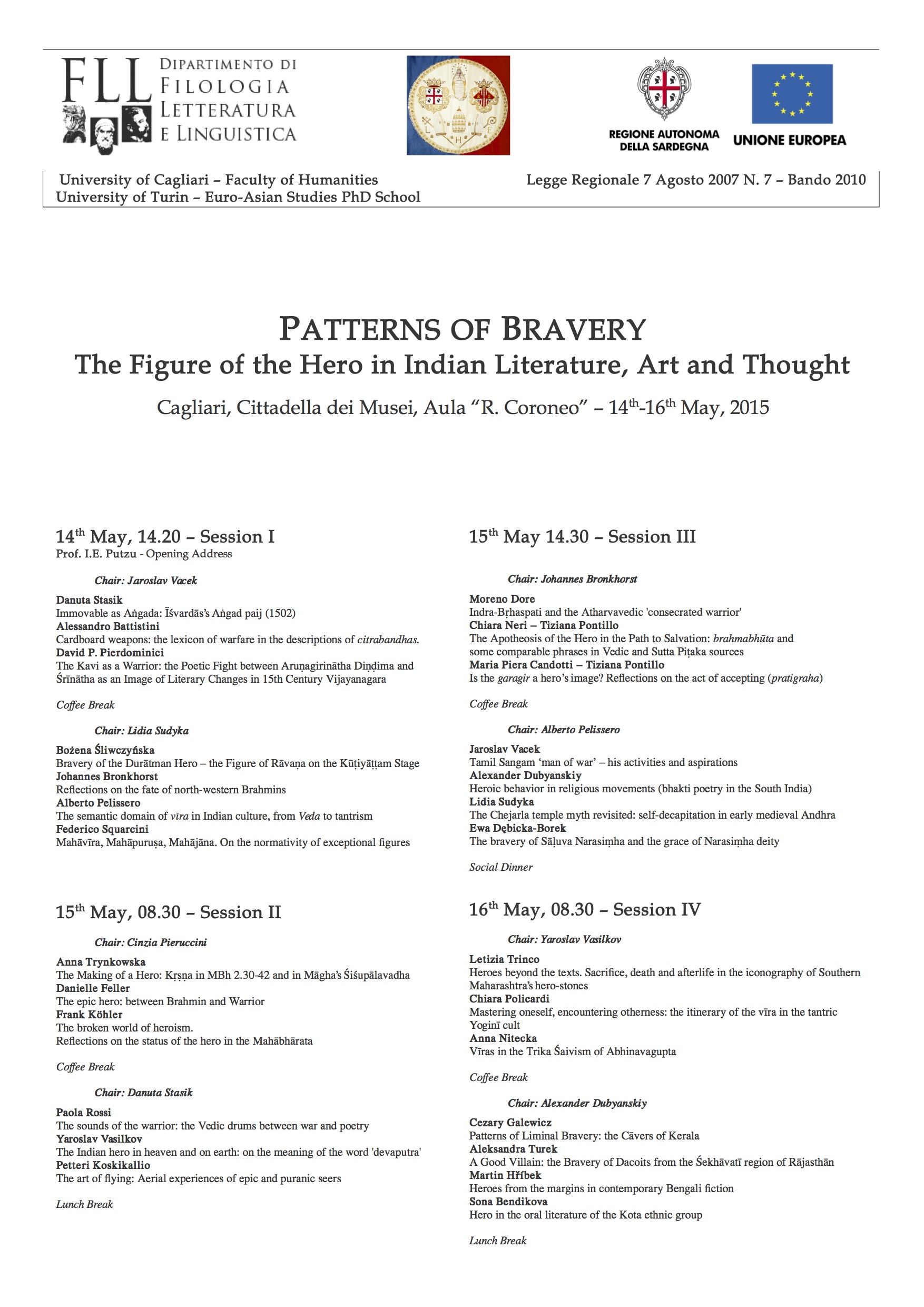

Patterns of Bravery. The Figure of the Hero in Indian Literature, Art and Thought

Cagliari, 14th--16th May 2015

Tiziana Pontillo signalled me the conference mentioned in the title. You can download the flyer here.

From the point of view of methodology, let me praise T. Pontillo for the fact that she will give two joint papers. Let us all learn from each other and dare more cooperative work (if we enjoy it)!